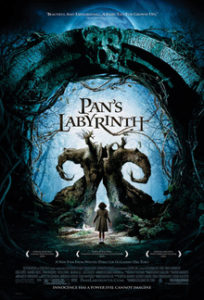

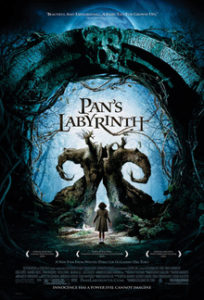

An evil stepparent. a lost princess, a magic book. a dangerous maze, a series of challenges, a terrible choice, and a world of war and woe. Guillermo del Torres’ movie, El labirinto del fauno (Pan’s Labyrinth) operates at many levels and in many ways: war story, horror flick, fairy tale, coming-of-age movie. Critics are raving about it; at Rotten Tomatoes, it has a 96% “fresh” rating, the highest I think I’ve ever seen.

An evil stepparent. a lost princess, a magic book. a dangerous maze, a series of challenges, a terrible choice, and a world of war and woe. Guillermo del Torres’ movie, El labirinto del fauno (Pan’s Labyrinth) operates at many levels and in many ways: war story, horror flick, fairy tale, coming-of-age movie. Critics are raving about it; at Rotten Tomatoes, it has a 96% “fresh” rating, the highest I think I’ve ever seen.

While I wouldn’t go so far as to call Pan’s Labyrinth a masterpiece, it’s a powerful film, loaded with provocative, profound spiritual metaphors, and it isn’t easily forgotten. It may well become the most successful foreign film in the US since Life is Beautiful, and could even surpass it.

Our protagonist is Ofelia, a 12-year-old girl being taken by her mother to live in a small army post commanded by her new stepfather, a sadistic captain in Franco’s regime determined to crush the remaining opposition in the foothills of the Pyrenees. If you ask a group of people to name a brutal European dictator who came to power in the pre-War period, you’ll hear the names of Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini, but probably not Franco, the Fascist who escaped Allied attack and continued to brutalize his people for four decades.

Ofelia’s world could hardly be worse. Not only is she fatherless in an awful environment, but her mother cannot help her either… she’s not only enduring a difficult pregnancy complicated by another illness as well, but even worse, she’s suffering the paralyzing realization that the beast she just married is incapable of love.

The Challenge of “That Age”

In addition, Ofelia is at the brink of puberty, that precarious age balanced between the mysteries of adulthood, sexuality, and growing up on one hand, and holding on to childhood on the other hand. Given her circumstances, it’s not surprising that Ofelia chooses the comfort of her fantasies, and uses the magical presence of a huge and frightening stone labyrinth to walk straight into the world of symbol, mind, and spirit.

But it’s in fairy tales that the awesome powers of choice, life, and death become even more clear. Her labyrinth is not a refuge, but the fuel for the challenge in discovering her true identity. There Ofelia meets a frightening-looking, but apparently benevolent faun, who reveals to her that she is not really of this world, but is the reborn princess of a spiritual realm who has become lost. As in all good fairy tales, he gives her three tasks she must accomplish to realize her destiny, and a tool to help her accomplish her ordeals.

The coming-of-age aspect is key to understanding the mysteries of Pan’s Labyrinth; the need to make adult choices with no help from others is crucial. Symbolically, Ofelia’s coming of age represents the spiritual coming-of-age challenge before all of us. Can we find out who we really are? Are we of this world of circumstance, or are we spiritual creatures? Who is our true Father? Will we take the challenges necessary to find the answers?

The Magic Book

The tool the faun gives Ofelia is a magic book that describes what she must do. However, its pages remain blank unless she opens the book to read them alone. This seemed to me a marvelous metaphor for meditation… Our souls are opaque, unknown and unreadable to us, until we center into the quiet, and let Isness inform us with a wordless knowing. Not only does the book describe her tasks for her, but it also lets her know and feel the pain of others; at one time in which she consulted the book, the pages turned red to warn her that her mother was hemorrhaging at that very moment.

In the same way, meditation also enables us to sharpen our sense of connection with others to serve them with love… helping her mother through her illness becomes an additional task to the initial three.

The Power of Choice

Ofelia is warned by the chief housekeeper (Maribel Verdú, Y Tú Mamá También), whose name is Mercedes (“mercy” in Spanish) “to be wary of fauns.” Nevertheless, Ofelia continues to meet the challenges posed to her by the faun, each increasing in difficulty and danger. The final task is almost complete when she learns that it also entails shedding innocent blood. Here there’s a choice to be made: to continue to follow the voice that has been guiding her thus far, or to refuse to. The faun has become not only the voice of authority, but of trusted, beloved authority to her. It’s both friend and father figure, and can be seen as a metaphor for the common religious view of God as the Authority on high. Has Ofelia been duped? Is the faun really a devil? Or is it the Demiurge, the twisted god who creates worlds of strife and confusion and demands obedience over everything? Is she even of the spiritual world at all? Was it all just lies? Where can she turn now?

In this pivotal scene, Pan’s Labyrinth re-examines the Abraham and Isaac story the same way Pleasantville re-examined the Garden of Eden story. We’re told that Abraham was a hero of faith because of his obedience, but this movie makes us wonder if obedience was really the highest virtue on God’s list. If Abraham had said, “Hell, no!” would his faith have been less, or would he have been tuning into a faith in mercy and life, which God ended up showing him anyway?

(In God is a Verb, Rabbi David Cooper states that many rabbis consider Abraham a greater hero than Noah not for his obedience, but because he had the guts to stand up to God concerning the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. In contrast, Noah meekly enabled God to destroy the world by quietly cooperating with his ark-building.)

In the parallel “real-world” story, a doctor bravely stands up to the Captain and says that blind obedience is something only the Captain could do… that he must obey his conscience.

Choice is ultimately what defines us all. It’s the vessel through which we navigate the manifest world. We are one soul, but the one makes many different choices through our wills. And all choices have consequences: Labyrinth explores their weight brilliantly. Some people pay dearly for their choices. Others never choose wisely at all.

But choice must be informed by knowing the truth, as Ofelia endeavors to. We must tune into the deepest parts of our hearts, where the soul can be informed directly by God, and remember where we really came from, and who our real Father is. Then choice becomes the power that turns spiritual children into spiritual adults. As Jed McKenna remarks in Spiritually Incorrect Enlightenment, “often a seventy-year-old is an eleven-year-old with fifty years of experience.” We need more people that can make adult decisions for compassion, rather than childishly following the forces of authority who tell us their agenda is always for the best. “Only a little blood will be shed in this war. It’s for our own good.” Our choices must move us into living consciously for justice and mercy.

A caution

Unlike other fantasies, Pan’s Labyrinth alternates between the make-believe violence of the fantasy landscape, and the shocking violence of the real world. While this serves to further contrast Ofelia’s path of trust and the Captain’s path of fear, some scenes should have been deleted or heavily edited. The depiction of violence is extreme. Do not bring the kids. But do bring your heart and mind. They will be well fed.

My friend Darrell Grizzell has written a contrasting review.

Technorati Tags: Pan’s Labyrinth, faun, movies, choice, El labirinto del fauno

Once I watched an exciting past episode of Lost with a friend who also enjoys it, but who couldn’t stop thinking about it as he watched it. An action scene begins, and he shouts, “No way! The water wouldn’t have risen that high!” or “I really doubt Kate would’ve said that; that was off.” Fine. But that’s looking at the show, interpreting it, critiquing it—not experiencing it. He’s enjoying it in a certain way, but I wonder if he wouldn’t enjoy it more to simply enter the world that’s presented on screen for 45 minutes, and leave the analysis aside until the end credits. (I know I do!)

Once I watched an exciting past episode of Lost with a friend who also enjoys it, but who couldn’t stop thinking about it as he watched it. An action scene begins, and he shouts, “No way! The water wouldn’t have risen that high!” or “I really doubt Kate would’ve said that; that was off.” Fine. But that’s looking at the show, interpreting it, critiquing it—not experiencing it. He’s enjoying it in a certain way, but I wonder if he wouldn’t enjoy it more to simply enter the world that’s presented on screen for 45 minutes, and leave the analysis aside until the end credits. (I know I do!)