a Jules Vernes-ian adventure for modern mystics

Two years ago I re-read The Chronicles of Narnia for a book club. And while it definitely still has some wonderful moments and unforgettable images, Narnia disappointed me this time around, truly a slog at times–sometimes off-putting to me, its mostly-absent God who only visits Narnia every few centuries seemed more deistic than Christian, the total separation of creature and Creator seemed a reinforcement of bad Sunday School teaching, and a near-total disinterest in peacemaking and justice betrayed a tremendous missed opportunity.

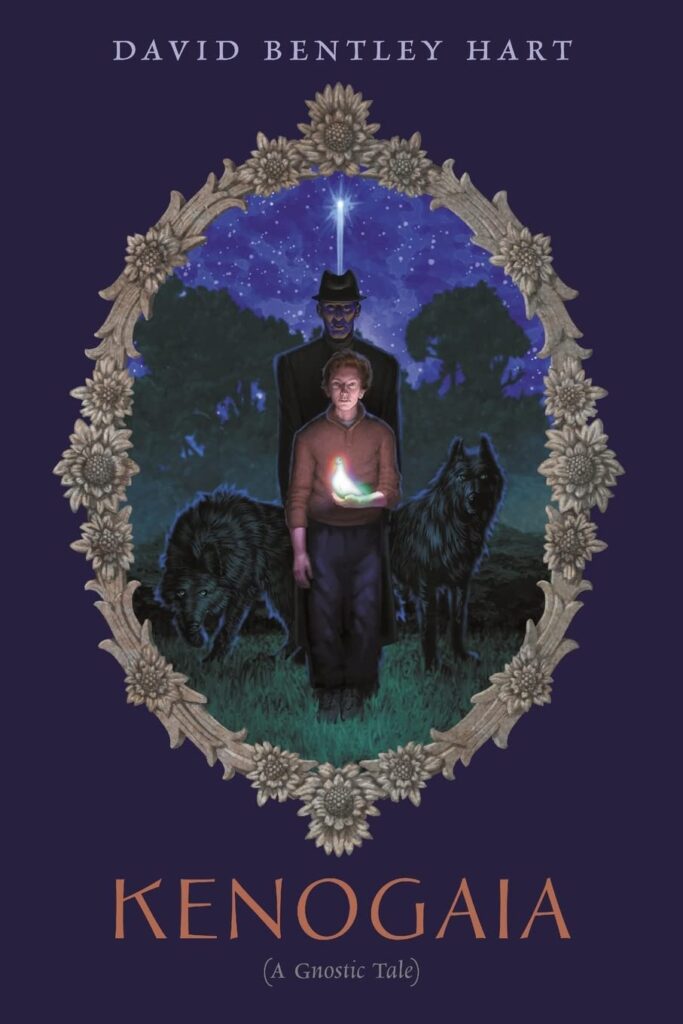

Reading it this time, decades after I had left my youthful Fundamentalism behind, I wished that Narnia had a deeper spirituality. David Bentley Hart’s Kenogaia (A Gnostic Tale) now fills the youthful spiritual adventure spot in my heart that Narnia once did.

Kenogaia is the world where Michael Ambrosius is growing up, a fantastic world reminiscent of a Jules Vernes-ian Europe, but with unique technology: although electricity remains undiscovered and land travel is limited to carriages, manipulation of wind, air, and minerals has resulted in “anemophones” which enable people to speak across distance, aerial barges for travel and transport, and the crystals in “phosphorions” give artificial light, among many other inventions in this richly-envisioned world.

Astronomy (“ouranomony”) is vastly different from ours; not only do its people believe that the moons, sun, and planets travel across the sky in nested, transparent crystalline spheres as we used to imagine, but they know it as an indisputable fact: Kenogaians can see the gears that move the spheres, and so praise the “Great Artisan” for his handiwork.

The action opens with Michael’s father confiding his discovery of a new star—rapidly approaching Kenogaia—to his son. This seems impossible given the nature of the spheres, but his illegal telescope confirms the reality, and he charges Michael to keep the new star utterly secret, since in this world, knowledge and belief are controlled by an authoritarian fusion of science, religion, and psychology, and “therapy” is a dreaded form of punishment. Soon his father is arrested, and a few weeks later Michael learns that the “star” is bringing a mysterious visitor to Kenogaia.

Kenogaia is loosely inspired by a beautiful poem, The Hymn of the Pearl, found in The Acts of Thomas, an early gnostic Christian writing. A flowing translation of the entire poem (presumably by Hart himself) is presented as epigraphs for the major parts of the book. The Hymn of the Pearl tells of a child’s journey to a strange land to seek a stolen, priceless pearl and return it to his homeland. Hart skillfully uses the essence of the journey as the plot’s foundation, and avoids any temptations of trying to use Pearl too literally. The protagonist of the journey, is the visitor, Oriens, who also appears as a child. Michael and his friend Laura commit themselves to protecting and aiding Oriens on his journey while they also search for Michael’s father.

Humor counterbalances the adventure in delightful ways. A comical police briefing had me laughing out loud, and reminded me of Monty Python at their best. Those already familiar with David Bentley Hart probably know that he owns one of the largest vocabularies in North America and isn’t afraid to use it. It’s in villainous pedantry and smugness that Hart lets his arsenal fly, and to great effect.

The story is tremendously satisfying, like a pleasurable encounter with a new cuisine at a good restaurant. Young people who read the book (I hope there are many!) will enjoy the tale. Adults may fear that the vocabulary is too much for young readers, but I don’t think so. Kenogaia is demanding, but it’s easier to read than classics like The Three Musketeers or Robinson Crusoe. (Adults are more likely to stumble with looking up meanings of unfamiliar words than kids.) And on the plus side, adults might contemplate the rich symbolism of Kenogaia and its spiritual implications. Anyone already on a mystical path will appreciate it deeply.

Kenogaia have some flaws, however. Two minor nits: Michael seems a little too mature and eloquent to be a thirteen-year-old (their years seem to be like ours), and Laura has too little to do.

More seriously, Kenogaia is insufficiently edited. Its 420 pages are printed in a rather small type; in a more common size we would be looking at 500 pages, and there simply is not enough story here to justify that amount of verbiage. Kenogaia is not Dune! Almost every descriptive paragraph could be trimmed (often substantially), and irrelevant details of what insignificant characters do in the background constantly interrupt more important actions at the forefront, delaying the action, inundating the reader with tsunamis of detail. Editing—that difficult and dying art of eliminating the good to illuminate the best—could turn Kenogaia from a delightful experience to an unforgettable one.

Currently, Kenogaia seems to be print-on-demand; it deserves the boost of wide publication and the chance to outshine its companions on bookstore displays. Perhaps a second, tighter edition could find wider distribution. It saddens me to think it may languish in obscurity. DBH, if you’re reading this, thank you for your beautiful work. May this pneumatagogue fly!

Kenogaia (A Gnostic Tale) David Bentley Hart, Angelico Press, 2021